The 1893 World's Fair

The Fair

The World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 was held to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus' discovery of America in 1492 and to showcase the fruits of man's material progress and the achievements of Western civilization.

The fair had a profound effect on architecture, sanitation, the arts, Chicago's self-image, and American industrial optimism. The exposition covered more than 600 acres (2.4 km2), featuring nearly 200 new (but purposely temporary) buildings of predominantly neoclassical architecture, canals and lagoons, and people and cultures from around the world. More than 27 million people attended the exposition during its six-month run.

The World's Columbian Exposition was the first world's fair with an area for amusements that was strictly separated from the exhibition halls. The Fair bore testimony to several firsts -- the Ferris Wheel made its first appearance, the United States Post Office produced its first picture postcards, phosphorescent lamps (the predecessor of fluoroscent lamps) were introduced, Cracker Jack and Quaker Oats were introduced for the first time, the first fully electrical kitchen including an automatic dishwasher was demonstrated, among others.

The Greatest Themes

The Exposition would not have been complete without a representation of the world's thought. Neely's History of the Parliament of Religions tells us that the idea of a series of congresses for the consideration of "the greatest themes in which mankind is interested, and so comprehensive as to include representatives from all parts of the earth originated with Charles Carroll Bonney in the summer of 1889". A committee was formed, and on October 30, 1890, the World's Congress Auxiliary of the Columbian Exposition was organized. Over the next two and half years elaborate plans were made involving an untold number of letters to and from all corners of the earth. The congresses, which finally met between May 15 and October 28, 1893 were twenty in all and embraced diverse things as woman's progress, the public press, medicine and surgery, temperance, commerce and finance, music, and -- "since faith in a Divine Power ... has been like the sun, a light-giving and fructifying potency in man's intellectual and moral development" -- religion. Of these congresses the Parliament of Religions was by far the most famed and widely heralded.

The Parliament of Religions

The Parliament was a unique phenomenon in the

history of religions. Never before had representatives

of the world's great religions been brought together in

one place, where they might without fear tell of their

respective beliefs to thousands of people. The proposed

objectives were (Ref. World's Parliament of

Religons, ed. John Henry Barrows, 1893)

1. To bring together in coference, for the first time

in history, the leading representatives of the great

Historic Religions of the world. 2. To show to men, in

the most impressive way, what and how many important

truths the various Religions hold and teach in

common...4. To set forth, by those most competent to

speak, what are deemed the most important distinctive

truths held and taught by each Religion and by the

various chief branches of Christendom...7. To inquire

what light each Religion has afforded, or may afford,

to the other Religions of the world...9. To discover

from competent men what light light Religion has to

throw on the great problems of the present age,

especially the important questions conncected with

Temperance, Labor, Education, Wealth and Poverty. 10.

To bring the nations of the earth into a more friendly

fellowship in the hope of securing permanent

international peace."

September 11, 1893

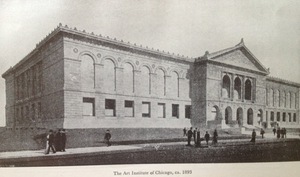

The Parliament of Religions opened on the morning of September 11, 1893 at the newly constructed Art Institute of Chicago (before it had started housing the art exhibits for which it is now famous). The delegates for the Parliament gathered at the Hall of Columbus which could accommodate 3000 people with standing room for at least a thousand more.

At ten o'clock, ten solemn strokes of the New Liberty Bell which was inscribed "A new commandment I give unto you, that ye love one another", proclaimed the opening of the Parliament -- each stroke of the bell representing one of the ten chief religions — Theism, Judaism, Mohammedanism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, Shintoism, Zoroastrianism, Catholicism, the Greek Church, and Protestantism.

Four thousand had crowded onto the floor and into the gallery of the Hall of Columbus waiting for the delegates to appear. At ten, the group of delegates in a procession entered the back of the auditorium, the crowd making way for it. Then beneath the flags of many nations and amid wave upon wave of cheers it marched down the center aisle and ascended the platform. In the midst of this array sat Swami Vivekananda, conspicuous, according to all accounts, for his "orange turban and robe," or, as put by another delegate, for his "gorgeous red apparel, his bronze face surmounted with a turban of yellow."

The first day, September 11, was devoted to speeches of welcome from the officials and responses by the delegates. Through it all, Swami Vivekananda remained seated, meditative, and prayerful, letting his turn to speak go by time and again. It was not until the afternoon session, and after four other delegates had read their prepared papers, that he arose to address the congress.

The electric effect on the audience of the first

words Swami Vivekananda spoke is well known. Neely's

History comments that when Mr Vivekananda

addressed the audience as 'Sisters and Brothers of

America,' there arose a peal of applause that lasted

for several minutes.

Mrs. S.K. Blodgett, who much

later became Swamiji's hostess in Los Angeles, recalled

I was at the Parliament ...When that young man got

up and said, 'Sisters and Brothers of America,' seven

thousand people rose to their feet as a tribute to

something they knew not what."

The applause that

had punctuated Swamiji's talk thundered at its close.

The people had recognized their hero and had taken him

to their hearts; thenceforth he was the star of the

Parliament.

The full text of his speech at the opening of the Parliament can be read here.

Vivekananda at the Parliament of Religions

One description of Swami Vivekananda at the

Parliament comes from the Chicago Advocate, a

journal that was not entirely favorable to him. In

certain respects, the most fascinating personality was

the Brahmin monk, Suami [sic] Vivekananda with his

flowing orange robe, safforn turban, smooth-shaven,

shapely handsome face, large, dark subtle penetrating

eyes, and with the air of one being inly-pleased with

the consciousness of being easily master of his

situation. His knowledge of English is as though it

were his mother tongue.

In addition to the plenary

sessions at the Parliament, Vivekananda addressed the

Scientifc Section several times. Unfortunately

the talks were not taken down and hence are missing

from the reports. Nevertheless, Dr. Barrows' book lists

the dates:

- September 22, Friday morning: Conference on Orthodox Hinduism and the Vedanta Philosophy

- September 22, Friday afternoon: with Mr. Merwin-Marie Snell conducted a Conference on the Modern Religions of India

- September 23: Conference on the subject of the Rinzai Zen on Japanese Buddhism

- September 25: The Essence of the Hindu Religion

The Chicago Inter Ocean of September 23

contains the following report: In the Scientific

Section yesterday morning, Swami Vivekananda spoke on

Orthodox Hinudism. Hall 3 was crowded to

overflowing and hundred of questions were asked by

auditors and answered by the great Sannyasi with

wonderful skill and lucidity. At the close of the

session he was thronged with eager questioners who

begged him to give a semi-public lecture somewhere on

the subject of his religion. He said that he already

had the project under consideration.

After the opening day, Swamiji again spoke on

September 15. His talk Why We Disagree can be

found in the Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda Vol.

1. On September 19, he presented his now-famous "Paper

on Hinduism". The Chicago Herald called his

speech one of the most interesting features of the

day.

It was in this speech that he laid out his

idea of a universal religion.

It will be a religion which will have no place for persecution or intolerance in its polity, which will recognize divinity in every man and woman, and whose whole scope, whose whole force, will be created in aididing humanity to realise its own true, divine nature.

On September 20, he spoke again at the end on Religion not the crying need of India On September 26, he gave a talk on Buddhism, the fulfilment of Hinduism According to Life, he spoke on at least three other occasions. On September 22, in Hall VII, he spoke at a special session organized by Mrs. Potter Palmer of the Woman's Branch of the Auxiliary, on Women in Oriental Religion. On September 23, he spoke before a session of the Universal Religious Unity Congress. On September 24, he spoke on "Love of God" at the Third Unitarian Church at the southeast corner of Monroe and Laflin.

Assimilation and not Destruction

On September 27, the final day of the Parliament, Swami Vivekananda gave his final address concuding it with the rousing call

... upon the banner of every religion will soon be written, in spite of resistance: ‘Help and not Fight,’ ‘Assimilation and not Destruction,’ ‘Harmony and Peace and not Dissension.’

If that call for assimilation and not

destruction

was relevant then, it is all the more

relevant today, and it is incumbent upon us to take the

message of assimilation, harmony and peace to heart. In

this year of Swami Vivekananda's 150th birth anniversary, the

Vivekananda Vedanta Society of Chicago invites you to

join us in a special program celebrating that call.

Chicago Calling

Credits:

Swami Vivekananda in the West, New Discoveies Vol.1, by Marie Louise Burke

Swami Vivekananda in Chicago, New Findings, by Asim Chaudhuri

Neely's History of The Parliament of Religions

Life of Swami Vivekananda, by his Eastern and Western disciples.